At the far end of the Archaeological Museum in Thrissur, tucked away from the better-lit galleries, there’s a quiet row of twelve stone slabs. Ten are Vīrakkal — hero stones — and two are Satikkal, sati stones.

The tradition of memorial stones in South India is one of the most enduring art forms of the peninsula. It stretches back over two millennia, from the 3rd century BCE through the early modern period. These were not tombstones in the Western sense; they were moral markers. Communities raised them to honor those who had lived — or died — in ways that exemplified virtues worth remembering: bravery (vira), loyalty, and, in the case of women, a kind of spiritual fidelity that came to be idealized as sati.

From the early historic period (around the 3rd century BCE) to the early modern era, the practice of erecting commemorative stones flourished across the peninsula. Hero stones (Vīrakkal) appear across Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Kerala, with the Deccan plateau yielding the richest examples. There, in a landscape defined by warrior lineages and feudal loyalties, the culture of valor memorialization took deep root. Sati stones (Satikkal) emerge later, around the 9th century CE, under the Chalukya, Hoysala, Pandya, and Chera polities, forming a parallel commemorative tradition that celebrated women’s fidelity within, I imagine, a patriarchal moral world.

It is important to note that these were not funerary markers in the Western sense. They were active ritual centers. Families and communities gathered around them for annual vira-puja — ritual offerings of light (deepam) and basil leaves (tulasi) — transforming them into sites of memory and moral instruction.

Each region leaves its own stylistic signature. Karnataka’s hero stones, for instance, unfold like miniature epics, each register narrating a moment in battle, a final duel, a soul’s ascent.In Tamil Nadu, many have been discovered in the Kongu/Coimbatore region. These stones sculptural programs emphasize dynamic combat scenes and less celestial imagery than those in Karnataka.

Kerala’s corpus, by contrast, is sparse. The stones preserved in Thrissur mostly originate from Palakkad, with one Vīrakkal from Wayanad. Compared to their Deccan counterparts, these examples are more restrained. They are smaller in scale, simpler in carving, and limited in narrative scope.

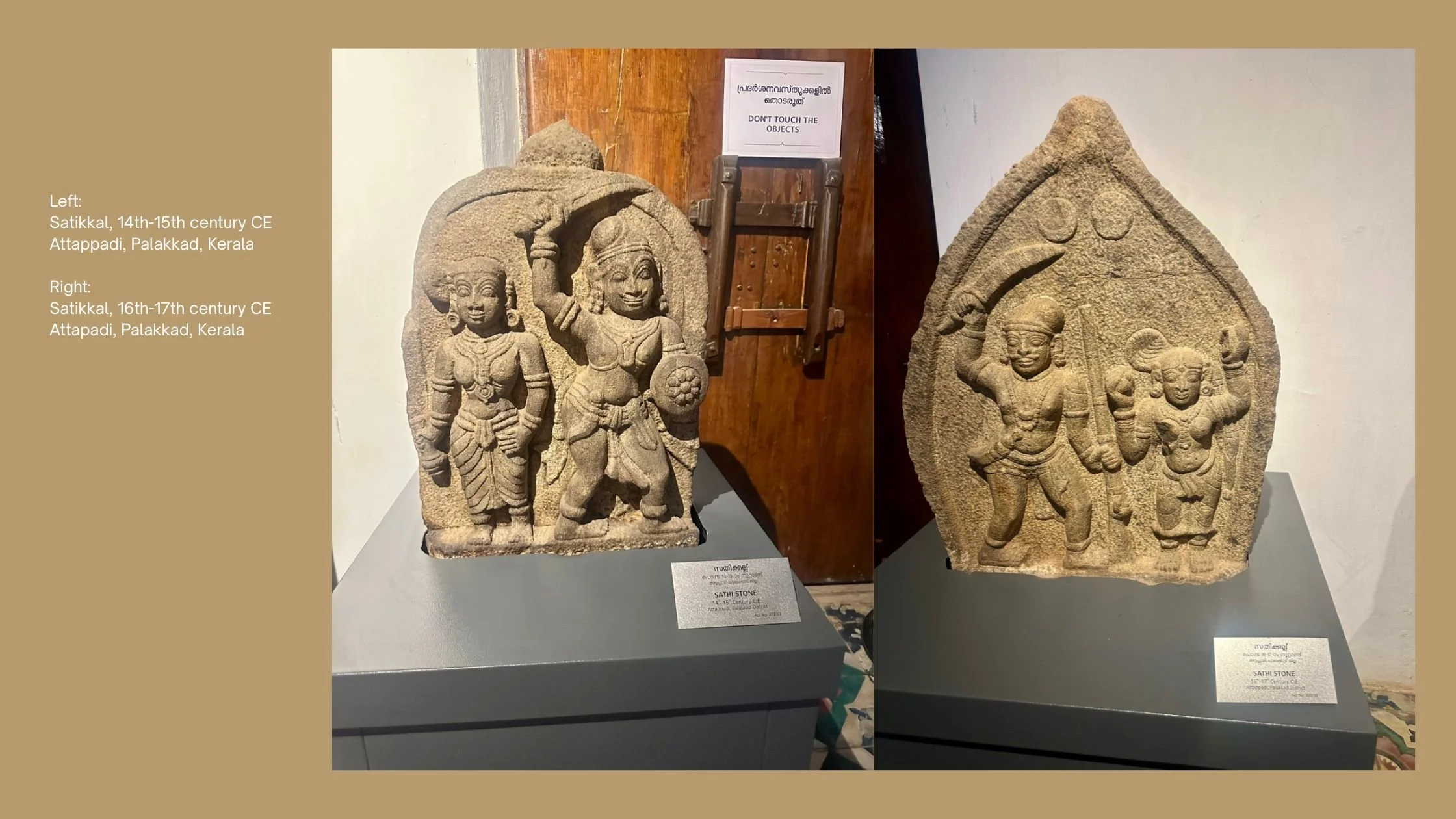

Among these are the two Satikkal pictured above, tentatively dated to the 14th–15th and 16th–17th centuries. Both were found in Attappadi, Palakkad district. Their dating, if you ask me, is uncertain — and that in itself feels fitting. So much of women’s history sits in that gray space between record and recollection. But the iconography is unmistakable: a husband shown armed, perhaps mid-battle, and beside him, the woman who followed him into death — hands raised in gesture in one case, and both holding specific attributes that likely mark their devotion.

Art historian Anila Verghese, who has studied Vijayanagara-period memorial stones, distinguishes Sati-Vīrakkal by the dual presence of the armed hero and his wife — the former depicted in full martial regalia, the latter holding ritual objects associated with her act of devotion. Both figures are enshrined as moral exemplars, bound together in stone as they once were in life.

This is just the beginning of my research on these two Satikkal, but I hope to return to them soon — to “read” them more closely, to compare their visual elements, to trace what they reveal about Palakkad’s early modern world.

Would you want to see some of that comparison next, may be a closer look at the symbols and the stories carved into these stones?

FURTHER READINGS

Verghese, Anila, "Memorial Stones", in New Light on Hampi: Recent Research at Vijayanagara, Mumbai: Marg Publications 2001, edited by John M.Fritz and George Michell, with photographs by Clare Arni, pp.40-49.